Inside

/I played a game that haunts me. Not with gore, or a monstrous danger in the dark, or fear for my life, but a fear for that life’s possible reduced value, a fear of four walls, and wiggly mind-worms and mind-control hats. The game, this ludic poltergeist, invades my thoughts and begs me to come back, to continue to know it in every sense I can. After a couple playthroughs, I’m still mad with curiosity and obsessed with its beautifully eerie world and the powerless, little boy that mysteriously chooses to brave its terrors. I can’t stop thinking about Inside.

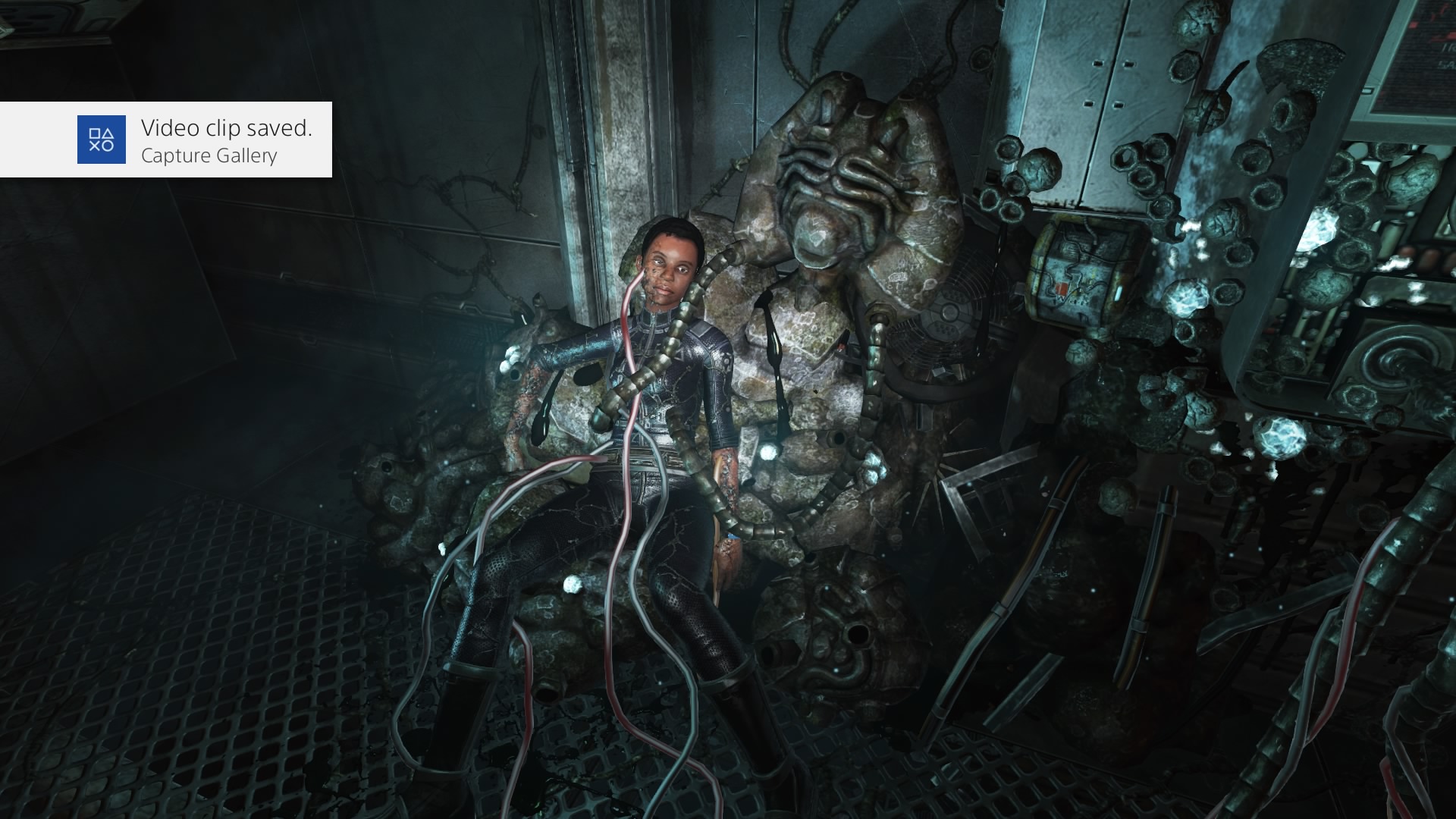

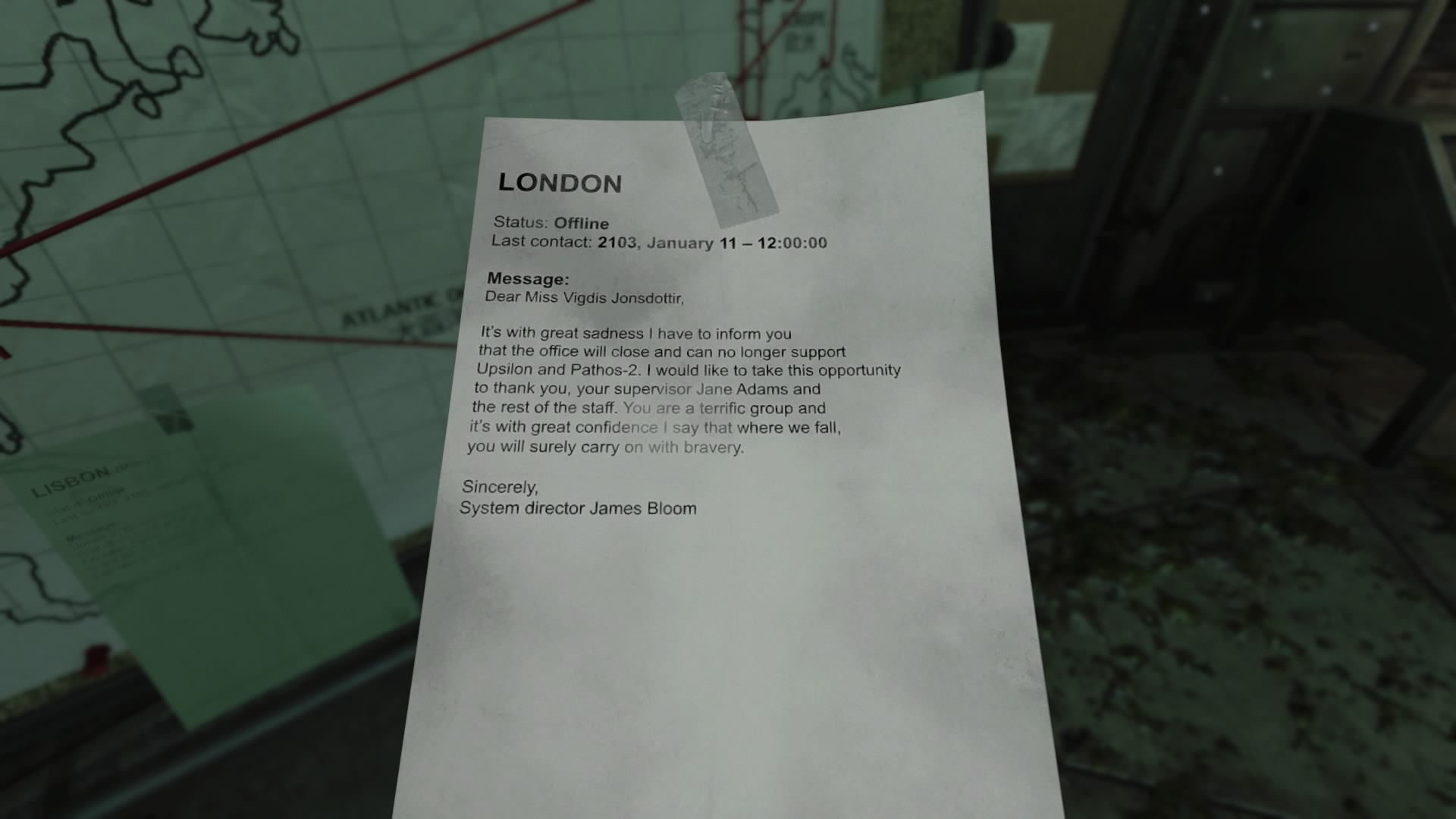

Inside is the second creation of Denmark-based Playdead, the independent developer responsible for the equally haunting and enigmatic Limbo (2010). Limbo is a monochromatic side-scrolling puzzle-platformer starring a little boy who journeys through a dangerous, surreal nightmare-scape. Inside also stars a little boy and plenty of puzzles, but is less figurative in both presentation and content, with full color and a more concrete narrative: a dystopic quest of curiosity. At the beginning of the game the little boy crawls through the brush of a dark forest to behold a large cargo truck, its carriage crowded with people standing in business attire. None of them stir as men with masks and flashlights shut the loading door and the truck slowly drives off. Then the boy follows the truck, avoiding the men and violent death by their bullets or dogs. Inside’s cryptic tale takes the child through forest, farmland, industrial ruins, and a city, revealing an ironhanded, cruel world. Every setting, object, and detail informs this world and expresses its depressing richness all the way up to its shocking end dripping with symbolism. When you get there, you may not not know exactly what to think; Inside holds no hands and offers no answers. It kept me up at night and made me jump right back into it the next opportunity I got.

At its core, Inside’s mechanics are enjoyable and a breeze to grasp; the boy can move and grab objects. The puzzles are fun and easily approachable, requiring just a bit of thought and experimentation without being exhausting or frustrating. This experimentation often leads to death, but smart checkpoint placements ensure players can jump right back into solving their current puzzle. Which is great, since you’ll die often, and these deaths are quietly disturbing, emphasizing the child’s innocence and powerlessness within the world’s merciless oppression. This is characteristic of Playdead’s game design, enabling them to generate a complex narrative within and through fun puzzles where death becomes a storytelling device rather than just a reset button. Solving Inside’s puzzles--and failing at them--feels great because the process itself illuminates the narrative and its themes; no moment, object, switch, or button is wasted.

Inside maintains a constant feeling of unease and wonder not only by its gameplay and images, but also through a stunning soundtrack that powerfully contributes to the game’s eerie nature. Composer Martin Stig Anderson fills Inside’s cavernous depth and mostly musical silence with a beautiful disquiet, using soft, undulating synthetic harmonies to beckon us forward into the frightful, mysterious, and terrifying. I felt Anderson’s music brought me closer to the child, to feeling his hope in rare, beautiful moments of freedom and his fear and panic in the face of tyranny and violence. It’s deceptively inviting, like an embrace with claws.

Inside is a short but memorable adventure, my first playthrough an engrossing two hours of blinkless awesomeness and unashamed mouth-breathing. This is a game that will stand the test of time as one of the greats, a deep expression of some horrors and hopes of the human experience. Not to mention that it’s simply one hell of a trip.

Marmoset’s Brew: Bourbon. It's bold, something you take your time with. And that flavor sticks around for days.