Final Fantasy Tactics: The Ivalice Chronicles Beginner Tips

/I love me a good RPG turn-based, tactical RPG. Give me a deep character and skill system with the ability to create my own builds and strategies amongst a roster of characters and thoughtful, challenging combat, and I’m a happy guy. Final Fantasy Tactics: The Ivalice Chronicles is a beautiful semi-remake of the original 1995 title, complete with all its depth and reasonable difficulty (seriously, though, it’s known for being tough). If this is your first time in Ivalice, you might find yourself unprepared for certain fights or uncertain where to start; I’m here to help, my friends! Take a gander at this lovely list of tips that will prepare you for anything that comes your way, without straight-up solving the game for you.

Get the JP (Job Points) Boost passive bonus for all your characters. You’ll have to unlock this skill using the Squire class, which is conveniently available at the beginning of the game. It is arguably the most useful ability in the game if you want to make the most of your time grinding to unlock abilities, and you will have to grind for JP to access the most useful abilities for each job. EXPERT TIP: switch this passive out for something else when jumping into story encounters; you don’t need extra JP in these fights, you need your characters at their strongest and most capable.

To make the most of grinding in random encounters, consider using low-damage abilities like Throw Stone to milk JP without killing the last enemy. Restore that enemy’s health with magic or items to keep them alive and soak up all that JP. It’s not the most fun thing to do, but you’ll find your characters can easily have hundreds of JP after a relatively short bout. Make the most of your grind, friends.

Save before every story encounter. These tend to be much tougher than random encounters, and some locations launch back-to-back fights without an ability to grind in between. Consider this your main save file that you can always go back to if things are too tough or if you otherwise make a mistake.

In those sequential story encounters, if you are given a chance to save, do not overwrite your main save. Seriously, some of these fights are very tough if you’re unprepared, so it is very easy to trap oneself in an unwinnable fight, therefore forcing a complete game restart.

Pay attention to brave and faith stats. Characters with higher brave do more physical damage, so are more effective with classes like Knight and Ninja. Higher faith leads to higher magic damage (or healing) for spells from classes like Black Mage, White Mage, and Summoner. Keep in mind faith goes both ways; a character with low faith will do low spell damage, but will also receive less spell damage or healing from spells. If you’re wondering why your Flare is doing to little to that one enemy, perhaps their faith is low. A fun exploit; reduce a character’s faith to 0, and they are immune to spell damage. How about that?

Steal stuff. Particularly during story encounters. You can easily procure gear earlier than shops offer it, saving you money and giving your team an edge, and it’s one of the only ways to get some of the rarer equipment. You can analyze enemies to see what they have equipped, but make sure to check that the enemy doesn’t have the Sticky Hands ability, which prevents theft. Even if that weapon isn’t juicy, stealing it means your enemy can only attack with their bare hands, transforming classes like Knight, Dragoon, Ninja, or Samurai into cuddly teddy bears (skills that require specific equipment, like the Samurai’s Bushido ability, also become useless!). With that said, don’t use the Knight’s equipment break skills on enemies with equipment you want.

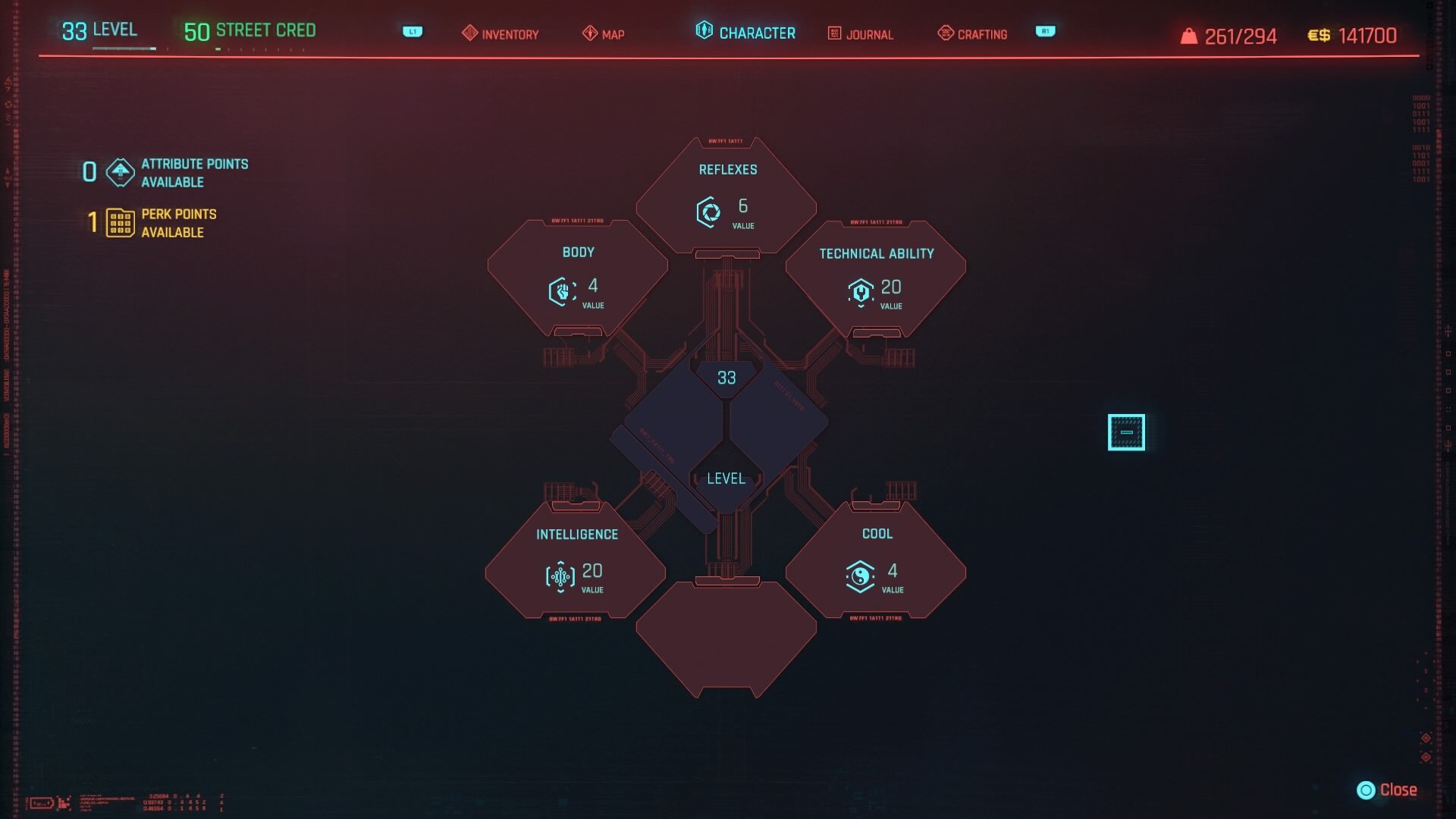

Character’s stat increases are dependent on the job they have when they level up. Someone who’s been a Knight for the last 30 levels will have far more health than someone who’s leveled up as a Black Mage. This is somewhat under-the-hood and really only matters if you’re a min-maxer, but it does mean you could minimize how many character levels someone gets in a class you only have them in to unlock a new class or to get a specific job ability. If this is a bit much for you, ignore it, it’s not a game-breaker.

Unique story characters, like Agrias, Mustadio, and the mighty Cidolfus, have higher stats than your cookie-cutter party members. Their Squire class is also replaced by a class unique to them, giving them some powerful and unique abilities. These characters can easily supplant your other party members mid-to-late game, unless you want to give yourself the challenge of not using those unique characters. I recommend trying that on a second playthrough though, because if this is your first Tactics foray, you’ll want all the help you can get. Expert Tip: do not underestimate the awesomeness that is Mustadio.

Mix and match job abilities to maximize each party members’ utility. Want a dual-wielding Knight? Learn the dual-wield ninja passive and slap that puppy on, no matter what class you are. Want to pump up your monk’s HP with heavy armor? Use the knight’s heavy armor passive. Your ninja can cast time magic, and that geomancer can double as your long-range healer with white magic or throw item. Don’t underestimate mobility skills that increase your lateral and vertical move ranges, which can increase the threat posed by your melee-based characters. In short, mix things up.

Don’t let characters die. When a character loses all Hit Points (HP), they will pass out. That’s fine. A counter of 3 turns begins ticking down to their permanent death as they bleed out. That’s not okay. Losing a character permanently is painful, not only because you might lose some sweet gear, but especially considering the amount of time it takes to build these suckers up across all the jobs. If you lose one, reload that aforementioned main save file and give the fight another go.

There are so many more tricks, strategies, and secrets to discover, so keep your eyes and mind open, but with these tips you’re ready to tackle all the wonderfulness that is Final Fantasy Tactics. Enjoy, and watch those flanks!

If you have any tips of your own, feel free to add them below for the community!