Helldivers 2: Fun as Hell

/That’s right folks, Drunken Marmoset is back reviewing games, and the first we’ve chosen is a doozy. Arguably the biggest game of 2024 (so far), there’s no better place to get this website back on track informing the wonderful masses than this beast of an online multiplayer game.

It’s been years since I’ve felt passionately about any online games. I’m older (30’s is still young, though, folks), I work hard, I like having the control my single-player games offer. Keeping up with other players is often daunting for me; I’m not the competitive champ I used to be. Then came along Arrowhead Games’ Helldivers 2, and with it a sense of confidence and excitement that I haven’t felt since my college-era gaming days. It has been a great experience because of its riveting gameplay, impressive emergent storytelling, and generally fun and reliable community.

The core of the gameplay here is all about teaming up with other players to manage swarms of enemies while accomplishing an assortment of missions. At the center of my love for Helldivers 2 is the horde-murdering fantasy that’s invaded and occupied my overactive imagination since childhood. The few-versus-many hero and horror stories of Helldivers’ inspiration Starship Troopers, The Lord of the Rings’ orcish attacks on Helm’s Deep and Gondor, and the good ol’ Zerg rush of Starcraft left me with a deep-seated hankering to fight throngs of overwhelming and horrific force that lives with me to this day. Few games, like the aforementioned Starcraft, have scratched this particular itch in all the fantastic ways that Helldivers 2 does, capturing the intensity, unpredictability, and high pressure of fighting off legions, while making one feel like a single small piece of a much larger force.

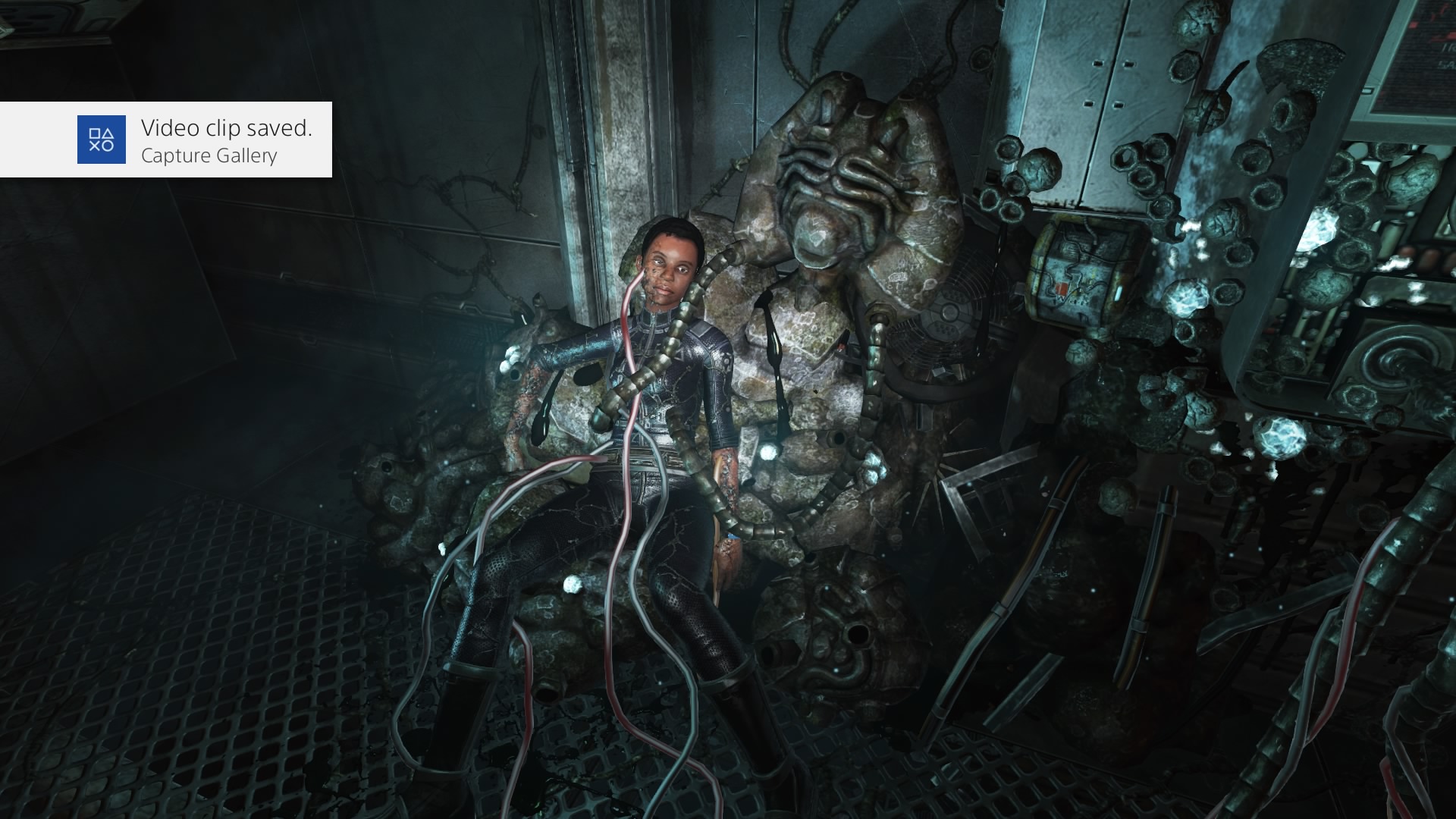

The struggle of fighting overwhelming odds has never been more cinematic or visceral. A highly customizable third-person camera guarantees a fantastic view of truly dramatic chaos; massive explosions rock the screen as they tear through giant bugs and automotons, allies’ gunfire zips above my prone body as I desperately crawl away from encroaching danger, all the while landscapes as various as deserts, jungles, swamps, and tundra gleam under red, setting suns. Thick fog, unpredictable earthquakes, and violent firestorms add their own beauty and challenges to the battlefields. Every mission feels incredibly grandiose and personal at the same time.

One can expect an assortment of firearms and grenades, which all feel great and work differently enough to make for fun and varied strategies, but it is strategems that give Helldivers 2 its unique strategic spice. Strategems, this shooter’s version of “abilities,” present a plethora of tactical options like support weapons (machine guns, anti-armor weapons, personal shields and drones), automated turrets, air- and orbital-strikes, gift players many ways to damn the flood and mete out impressive destruction. The input demand for each, directional inputs much like a code, creates a wonderful tension when threading through groups of enemies that a simple single button press couldn’t. It’s a delight hearing other players’ characters call out the strategem they’re summoning, seeing the red and blue beacons and watching as equipment pods fall from orbit or multiple explosions from an airstrike rip through a cadre of enemies. Exploring these options and learning how to utilize them to highest effect is a linchpin of Helldivers 2’s action, elevating it from what could be a simple player-versus-environment cooperative shooter to something special. And accidentally murdering your teammates with strategems makes for some dramatic–and often hilarious–“oops” moments.

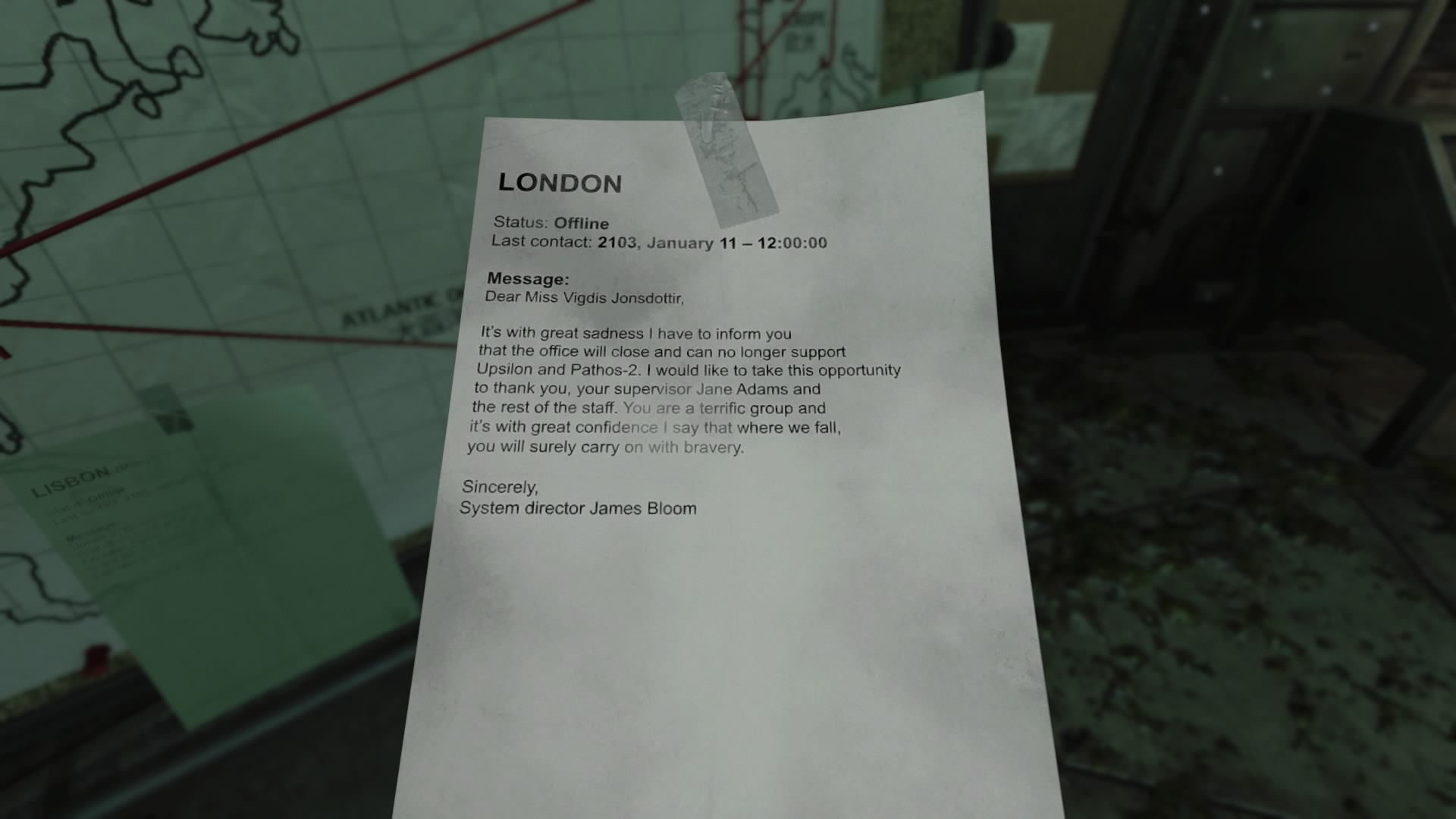

All of this in-the-moment badassery intermingles with a compelling gameplay loop and fantastic live-service. At its most basic, the game offers multiple mission-types, from simple kill-these-many-enemies skirmishes that can take 10-12 minutes, to larger 40-minute missions with multiple objectives. Players are currently engaging two battlefronts against very different enemies; the Terminids, bug-like creatures that most resemble the aforementioned nemeses in Starship Troopers and Starcraft, and the Automotons, a robotic force that operates more like a conventional army with lasers, missiles, tanks, and mechs. The community contributes to advances and successful defenses of each battlefront, and every week Arrowhead adjusts community objectives based on how these battlefronts are doing. There’s something special about not only working in a squad to complete objectives in a single sortie, but also contributing towards capturing the planet as a whole, or defending it, or some other metric like killing 2,000,000,000 (that’s right, 2 billion) enemies.

New strategems are even linked towards the success of some of these community goals, such as mechs (successfully unlocked by the community) or anti-tank mines (so far still unlocked due to operation failures). This allows for some powerful emergent storytelling, where the progress and history of the war is based on the performance of the community, but also motivates that community to cooperate and support one another. Fronts ebb and flow, with some real community losses already logged.

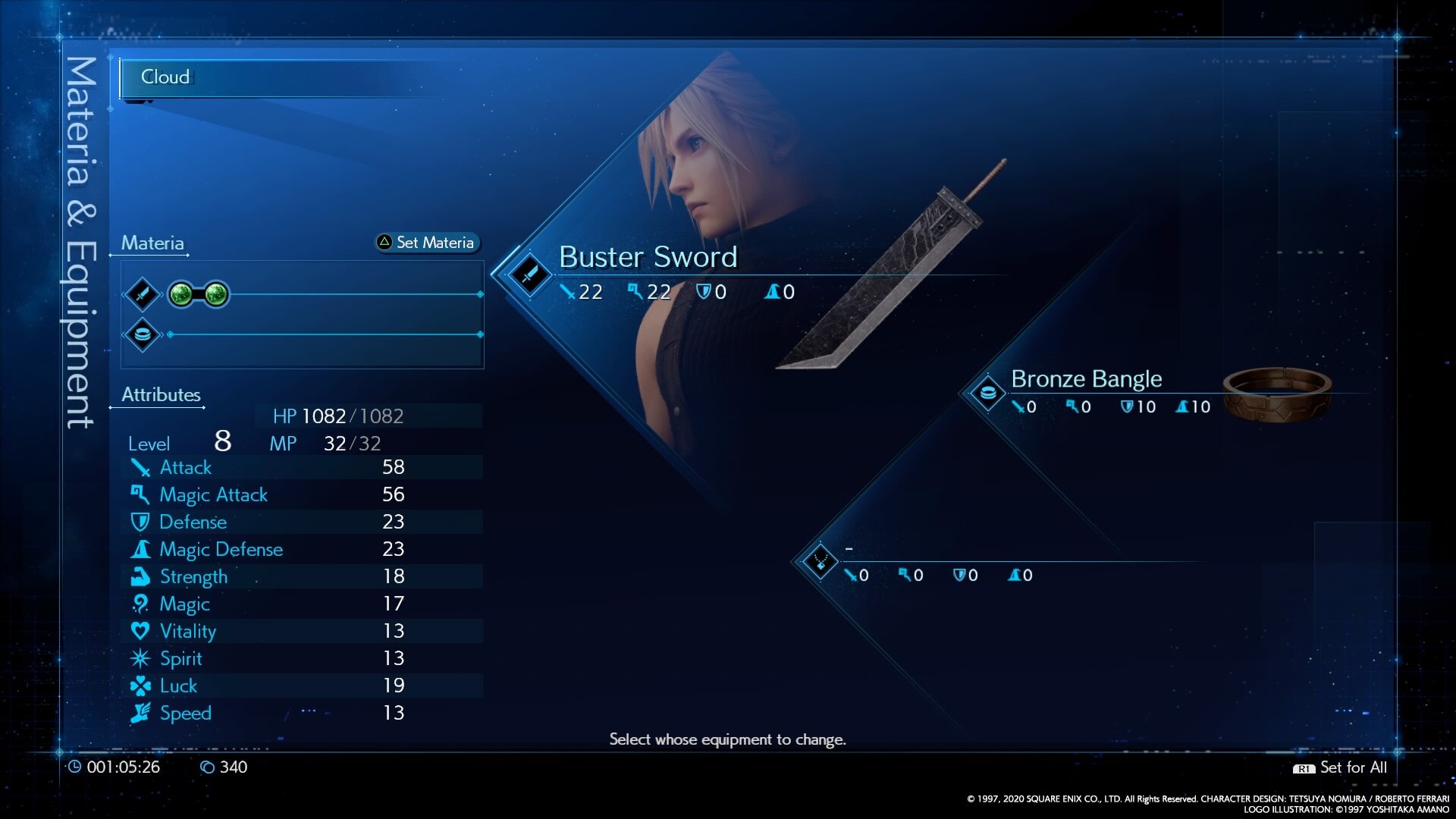

On top of all that is a simple economy for unlocking strategems, armor, weapons, and various upgrades. Experience and credits are rewarded when finishing missions; level progression grants access to certain features, mostly strategems, and credits buy strategems for permanent use. Samples are harder to come by, collected on the ground during missions, and unlock upgrades to your ship that benefit strategems, like reducing cooldown times or increasing turret ammunition or health. Rarer samples require playing the game at higher difficulties, so be prepared to brave missions with more objectives and tougher enemy types if you want to unlock the best upgrades. Finally, clearing operations–often a collection of 3 missions–award helldivers with medals which are spent on warbonds. Warbonds unlock primary and secondary weapons, grenade types, and armor sets that cater to different playstyles. There’s plenty to unlock, and it's fun and simple progressing through each track.

A note about warbonds. Each warbond has tiers of unlocks to progress through, but only the default warbond is available at the outset. Other warbonds require super credits to unlock. Super credits are available in-game, found in missions or awarded within warbonds themselves, but are also the purchasable currency. It’s easy enough to purchase the first warbond unlock with found or awarded supercredits, but after that getting additional supercredits can feel like a slog. You don’t need to spend a dime above the purchase price of Helldivers 2 to unlock everything in the game, but the time it takes to collect the right amount of supercredits is noticeable. Not everyone will appreciate this limitation.

Helldivers 2 is truly the first online game in many years that I just can’t put down. I can’t wait to see what our new major operation is every week, jumping into a mission and working with a squad towards unified goals is rewarding, and the gameplay is as exhilarating as it is thoughtful. This is a game to keep one’s eyes on, and I’m excited to see how it changes and evolves over time.

Marmoset’s Brew: Chipotle Ale. A familiar smooth, bold texture and flavor with the unexpected and unique kick of peppers that leaves a gratifying, but humbling, fiery taste in your mouth. It’s bold flavor keeps you coming back for more.